Kautilya, Machiavelli, Richelieu and Mazarin - part 16 : the Arthashastra

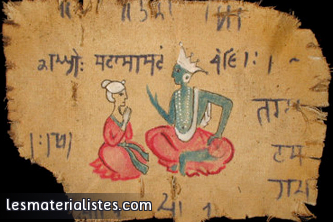

Submitted by Anonyme (non vérifié)We presented the Arthashastra, written by the Indian Minister Chāṇakya (c. 350–283 BC); let's see what are its arguments.

There is a state and an administration on one side, a science of politics on the other side. Hence:

“He, who is well-versed in the science of politics (…) plays, as he pleases, with kings tied by the chain of his intellect.”

“The source of the livelihood of men is wealth, in other words, the earth inhabited by men. The science which is the means of the attainment and protection of that earth is the science of politics.”

The king is just the vector of political science. But what is the state in itself? The Arthashastra gives seven principal elements of the state: “the king, the minister, the country, the fortified city, the treasury, the army and the ally.”

And here is its conception of the states's defense:

“If weak in might, a king should endeavour to secure the welfare of his subjects. The countryside is the source of all undertakings; from them comes might.”

“As between land with the support of a fort and one with the support of men, the one with the support of men is preferable. For a kingdom is that which has men.”

“Dependent on the fort are the treasury, the army, silent war, restraint of one's own party, use of armed forces, receiving allied troops, and warding off enemy troops and forest tribes. And in the absence of a fort, the treasury will fall into the hands of enemies. For, it is seen that those with forts are not exterminated.”

The German Carl von Clausewitz (1780-1831) produced conceptions that are finally the same. The masses are conceived as an instrument of the kingdom, just as the king who is an instrument himself.

The Arthashastra recomends to watch over everybody's actions: the making of the prince into a king, the ministers, the masses. Everything has to be controlled.

About the prince, it is for example said:

“If in the exuberance of youth, he were to entertain a longing for the wives of others, they should produce abhorrence in him through unclean women posing as noble ladies in lonely houses at night time. If he were to long for wine, they should frighten him with drugged liquor.”

Even the highest officials had to be secretly watched over:

“After appointing ministers (…) the king should test their integrity by means of secret tests.”

We can also read in the Arthashastra that the king not only has to send spies to watch citizens and the country people, but also to build alehouses for the spying to take place. Any recreation must be supervised by the state; public opinion has to be totally under control.

And as the Arthashastra is in all points a practical manual, it also gives a list of disguises for spies:

“The administrator should station in the country secret agents appearing as holy ascetics, wandering monks, cart-drivers, wandering minstrels, jugglers, tramps, fortune-tellers, soothsayers, astrologers, physicians, lunatics, dumb persons, deaf persons, vintners, dealers in bread, dealers in cooked meat, and dealers in cooked rice.”

The king has to make direct intervention, when it is necessary, to avoid further problems:

“Disaffection can be overcome by the suppression of the leaders.”

“Subjects contending among themselves benefit the king by their mutual rivalry.”

“An arrow, discharged by an archer, may kill one person or may not kill (even one); but intellect operated by a wise man would kill even children in the womb.”

“For the king, severe with the rod, becomes a source of terror to beings. The king, mild with the rod, is despised. The king, just with the rod, is honoured.”

Torture and assassination can prove useful if need be. Nevertheless, it is never to be forgotten that the rod is here to maintain the unity:

“The stronger swallows the weak in the absence of the wielder of the rod.”

This is why anger and lust are enemies of the kings, and:

“Mostly kings under the influence of anger are known to have been killed by risings among the subjects.”

We find again the notion that the king is an instrument of the state. It is the state that needs a king and ministers who are both strong and efficient. The growth of the general wealth is the goal of the administration.

In France, Louis XIVth didn't possess enough wealth to satisfy the masses, in particular because of the wars he initiated, and because of this, the affirmation of the kingdom was not complete. This created enough space for the appearance of an “integral nationalism”, later developed by Charles Maurras (1868-1952).

In France, Louis XIVth didn't possess enough wealth to satisfy the masses, in particular because of the wars he initiated, and because of this, the affirmation of the kingdom was not complete. This created enough space for the appearance of an “integral nationalism”, later developed by Charles Maurras (1868-1952).

With the failure of the feudal system that ended up breaking drown the whole mode of production, a whole romanticism was produced, based on royalism and the conception of an “organic state”.

The situation was different in India; Ashoka could maintain for a certain time a certain peace; he organized dispensaries for the people and for the animals, he was able to call for universalism. Here, the absolute monarchy developed openly the ideology of welfare.

This is the ideological (and idealist) core of absolute monarchy. Thus we can read in the Arthashastra:

“Material gain alone is the principal aim, for morality (dharma) and pleasures of the senses (Kama) are both rooted in material gain (arthamulau).”

The paradox is that this perspective helped, in the situation of India, the organization of Asiatic despotism, because of the defeat of the progressive forces and the come back of the feudal forces.

If we take a look at the situation at the time of the Arthashastra, we can see that the state owned extensive crown lands, all the natural resources, all the uncultivated lands, all the fishing , ferrying and trading rights, etc.

If we take a look at the situation at the time of the Arthashastra, we can see that the state owned extensive crown lands, all the natural resources, all the uncultivated lands, all the fishing , ferrying and trading rights, etc.

Cultivators were under the control of the state; when cultivation was not correctly operated lands were taken by the state and given to others or the village community.,

All the merchants' initiatives were controlled, the rate of profit was decided by the state, as were sales and distribution, and even working hours, wages, etc.; there was an administrator of trade routes and markets.

The state organized tanks and canals for the watering of the crops; it had the monopoly of wine and liquor-making, salt, boat and ship-building, while shipping-houses and weaving mills depended on administrators of the state.

The regulation of exchanges was also easy to understand:

“Whatever causes harm such as poison or alcohol is useless to the country, should be shut out. Whatever is of immense good like seeds and medicine not easily available should be let free of toll.”

This all meant the formation of a centralized market and unifying the country, which is the progressive aspect of the absolute monarchy. But in case of failure, this centralization as a whole would benefit a parasitic state based on feudal landlords.

This is what happened in India, where the Arthashastra had a deep influence until the 12th century, when it was lost; but in France, the state was directly taken up by the bourgeoisie as the nucleus of the nation, which raises and dies with capitalism.

Therein lies the importance of the 17th century as that of Richelieu, Vauban, Mazarin, Louis XIV, La Fontaine ...