Indian Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism - 9 : the appearance of the masses through the bhakti

Submitted by Anonyme (non vérifié)Hinduism succeeded in crushing Buddhism with bhakti, but the price was high, because that meant the integration of the devotion of the masses into the religious process itself. Here is how Kosambi describes this process, in “The Culture and Civilisation of Ancient India in Historical Outline”:

“The brahmins gradually penetrated whatever tribes and guild castes remained; a process that continues to this day. This meant the worship of new gods, including the Krishna who had driven Indra worship out of the Panjab plains before Alexander's invasion.

But the exclusive nature of tribal ritual and tribal cults was modified, the tribal deities being equated to standard brahmin gods, or new brahmin scriptures written for making unassimilable gods respectable.

With these new deities or fresh identifications came new rituals as well, and special dates of the lunar calendar for particular observances. New places of pilgrimage were also introduced with suitable myths to make them respectable, though they could only have been savage, pre-brahmin cult spots.

The Mahabharata, Ramayana, and especially the Puranas are full of such material.

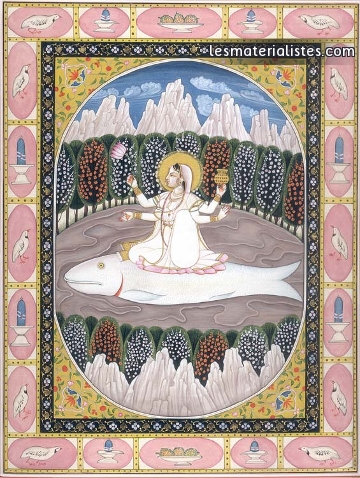

The mechanism of the assimilation is particularly interesting. Not only Krishna, but the Buddha himself and some totemic deities including the primeval Fish, Tortoise, and Boar were made into incarnations of Vishnu-Narayana.

The monkey-faced Hanuman, so popular with the cultivators as to be a peculiar god of the peasantry with an independent cult of his own, becomes the faithful companion-servant of Rama, another incarnation of Vishnu. Vishnu-Narayana uses the great earth-bearing Cobra as his canopied bed to sleep upon the waters; at the same time, the same cobra is Shiva's garland and a weapon of Ganesa.

The elephant-headed Ganesa is son to Siva, or rather of Siva's wife. Siva himself is lord of the goblins and demons, of whom many like the cacodemon [an evil spirit] Vetala are again independent and highly primitive gods, still in popular, village worship.

Siva's bull Nandi was worshipped in the south Indian neolithic age without any human or divine master to ride him; he appears independently on innumerable seals of the Indus culture.

This conglomeration goes on for ever, while all the tales put together form a senseless, inconsistent, chaotic mass.

The importance of the process, however, should not be underestimated. The worship of these newly absorbed primitive deities was part of the mechanism of acculturation, a clear give-and-take.

First, the former worshippers, say of the Cobra, could adore him while bowing to Siva, but the followers of Siva simultaneously paid respect to the Cobra in their own ritual services; many would then observe the Cobra's special cult-day every year, when the earth may not be dug up and food is put out for the snakes.

Matriarchal elements had been won over by identifying the mother goddess with the 'wife' of some male god, e.g. Durga-Parvati (who might herself bear many local names such as Tukai or Kalubai) was wife to Siva, Lakshmi for Vishnu.

The complex divine household carried on the process of syncretism; Skanda and Ganesa became sons of Siva.”

The process was a huge risk, giving birth to a mystical mass movement that rejected the clergy itself in the name of the mystical love.

Kabir (1440-1518) is one of the most famous leader of such a movement; his “path” is theorized in the Bijak (the “Seedling”), a compilation of mystical poems, still very famous. Here is an example of it:

“O servant, where dost thou seek Me?

Lo! I am beside thee.

I am neither in temple nor in mosque: I am neither in Kaaba nor in Kailash:

Neither am I in rites and ceremonies, nor in Yoga and renunciation.

If thou art a true seeker, thou shalt at once see Me: thou shalt meet Me in a moment of time.”“I am not a Hindu,

Nor a Muslim am I!

I am this body, a play

Of five elements; a drama

Of the spirit dancing

With joy and sorrow.”

Another important figure is Nanak (1469 – 1539), founder of Sikhism, who had a similar orientation in its rejection of both Hinduism and Islam, in the name of the devotion of the eternal truth.

Kabir and Nanak, among others, rejected the concepts of priests, of sacred texts, of becoming a yogi, of having dogmas: love and fusion with the “one” was a mystical “call”.

In such cases, there was a rupture with Hinduism, with the caste system, with any form of clergy. The mass mobilization was here at the core of things.

Even inside Hinduism, such tendencies existed, very powerful and marking their time. Chaitanya's vaishnavism went for example very far in the cult of Krishna, as did the poet Surdas (1528 - circa 1581), and the poetess Mira Bai (circa 1498 - circa 1546). Here is a poem of her:

“Unbreakable, O Lord,

Is the love

That binds me to You:

Like a diamond,

It breaks the hammer that strikes it.My heart goes into You

As the polish goes into the gold.

As the lotus lives in its water,

I live in You.Like the bird

That gazes all night

At the passing moon,

I have lost myself dwelling in You.

O my Beloved Return.”

And another one:

“In my travels I spent time with a great yogi.

Once he said to me.

“Become so still you hear the blood flowing

through your veins.”

One night as I sat in quiet,

I seemed on the verge of entering a world inside so vast

I know it is the source of all of us.”

We also find people like Eknath (1533–1599) and the very important Tulsidas (1532 – 1623), which formulated a “way” whereby God is considered both personal and impersonal, i.e. the goal of a mystical quest but also of a personal cult.

Bhakti has allowed Hinduism to gain the masses, but this meant their irruption inside religion itself.