Indian Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism - 7 : materialism, monism and the message of the Bhagavat

Submitted by Anonyme (non vérifié) The situation of materialism in ancient India was untenable. Materialism's two possible directions were blocked by either Hinduism or Buddhism.

The situation of materialism in ancient India was untenable. Materialism's two possible directions were blocked by either Hinduism or Buddhism.

Materialism had to overcome two hurdles. The first difficulty was to state that there is no soul, that only the body exists and therefore that humans do not “think”: there is only matter.

The second difficulty was to state that the universe is one, and that thought is the reflect of it, as an element of the totality.

However, both statements were impossible. Buddhism had already explained that the “souls” were an illusion, that there was no “individual”, and had called to deny the existence of matter and to dive into the Nirvana.

So, the materialist currents, which understood the emptiness of the concept of “individual” with a unique ego, had to take a mystical, religious exit.

So, the materialist currents, which understood the emptiness of the concept of “individual” with a unique ego, had to take a mystical, religious exit.

Any move towards a form of epicureanism was thus transformed into a negation of the soul, not in the name of matter, but as a negation of it as well as of the soul.

Then there was the question of thought as reflection of the universe through an “intellect”, to use the concept of Aristotle, Avicenna and Averroes.

But this orientation was also impossible, because Hinduism, and Shankara in particular, developed a concept very close to Buddhism: yes, there was only one universal intellect, but instead of being a reflection of the world, it was a reflection of God.

Thus, those who took this direction accepted monism, but it was a religious monism that negated matter.

One very important work here is the Bhagavad-gītā, the song of the prosperous one, dating from around the 5th century BCE. This work of 700 verses is the central part of the Mahabharata, the longest epic ever written in Sanskrit.

The goal of the Bhagavad-gītā is the plain destruction of Buddhism, materialism and the prestige of Ashoka.

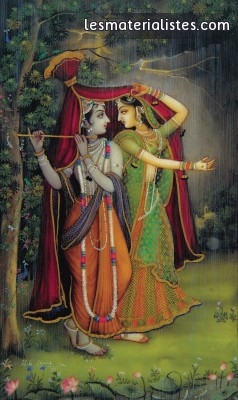

The story is the following: in a battle for the succession of a deceased king, Arjuna, the leader of one army, is dismayed to have to fight against members of his own family. He does not want a war. But his charioteer is in fact Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu.

The story is the following: in a battle for the succession of a deceased king, Arjuna, the leader of one army, is dismayed to have to fight against members of his own family. He does not want a war. But his charioteer is in fact Krishna, an avatar of Vishnu.

Vishnu tells him that only himself exists. Thus, Arjuna may kill, since he will not be really killing, as long as he understands that only Vishnu exists.

This means two things: on one side the Bhagavad-gītā defends a total monism, with only the universe existing as a “product” of Vishnu, all the thoughts being sub-products of the existence of Vishnu.

On the other side, the Bhagavad-gītā explains that the castes must be respected, that the Vedas are sacred, etc.

The reason why this work is such a strong weapon is because, in the renewal of the caste system, it appears that the real goal is not to be on top of society, but to leave the fake reality of this universe, to understand that only Vishnu exists. So, the masses will obey the ruling classes who are on top, but only as an illusion.

Let's quote some very interesting parts of the Bhagavad-gītā, which are really close to a materialist understanding of the thought as reflection of the eternal universe:

“The working senses are superior to dull matter; mind is higher than the senses; intelligence is still higher than the mind; and he [the soul] is even higher than intelligence.”

“That which pervades the entire body you should know to be indestructible. No one is able to destroy that imperishable soul. The material body of the indestructible, immeasurable and eternal living entity is sure to come to an end (…).

For the soul there is neither birth nor death at any time. It has not come into being, does not come into being, and will not come into being. It is unborn, eternal, ever-existing and primeval. It is not slain when the body is slain.”

“Although I am unborn and My transcendental body never deteriorates, and although I am the Lord of all living entities, I still appear in every millennium in My original transcendental form.

Whenever and wherever there is a decline in religious practice, O descendant of Bharata, and a predominant rise of irreligion — at that time I descend Myself.

To deliver the pious and to annihilate the miscreants, as well as to reestablish the principles of religion, I Myself appear, millennium after millennium.”

Vishnu “descends” when it is necessary: we can see that in the background, there is a wrong understanding of the principle of synthesis of a guiding thought in moment of “crisis”. And Vishnu is like the universe in the materialist understanding: eternal, without an end, etc.

Vishnu “descends” when it is necessary: we can see that in the background, there is a wrong understanding of the principle of synthesis of a guiding thought in moment of “crisis”. And Vishnu is like the universe in the materialist understanding: eternal, without an end, etc.

Because of this situation, materialism had to say: yes, Buddhism is right in saying that the individual ego is an illusion, but it is wrong to say that because of this, reality has no importance; and yes, Hinduism has understood that the universe is one and there is only one thought, but it is wrong in saying that thought comes from a god outside reality.

The situation was not ripe for such a materialist perspective, which only appeared more than 1000 years later with the Falsafa, and then Latin Averroism.

Materialism in ancient India was extremely weak. Although all materialist documents have been lost, we know the positions of the materialists through the criticisms made against them, which also often came with a summary of their views.

Shankara gives us the following informations about the conception of the so-called Lokāyatikas, the materialists:

“In the opinion of the Lokāyatikas, the foundation of the world is represented by four elements

- earth, water, heat, wind – and that is all; they don't recognize anything else.”

This means that according to ancient India's materialists, there was no soul, only matter (understood as the Indian four religious traditional elements). Shankara also sums up their position in this way:

“I am strong, weak, old, young - these characteristics are ascribed to the specific, particular body which is ātman, and there is nothing else besides it.”

From others authors, we know also in the same way that according to the Lokāyatikas there only existed earth, water, fire and air, which relationship is “called” body, sensory organs and objects. Nothing alive is maintained “beyond”, so there is no “beyond”.

It means that the Lokāyatikas were empiricists. They did not take into account the question of global unity of the universe or even the body ; they only believed what they saw and were so directly an equivalent of Epicureanism.

It was a practical direction, a primitive materialism. Shankara also tells us that according to the Lokāyatikas:

“With the help of the means accessible to perception, that is, agriculture, cattle breeding, trade, politics, administration and similar occupations, Let the wise one enjoy bliss on earth.”

This means that the Lokāyatikas were Epicureans directly connected to the kings. In Ancient India, the rulers wanted to act without any interference of the priests, so they came to support Epicureanism.

In this opposition within the ruling classes, the materialist intellectuals appeared as ideological weapons, through a phenomenon which is directly part of what we call political Averroism, starting notably with John Wycliffe (see Bohemia: the Hussite storm [to be published]).

This process went so far, that we find a direct equivalent of Machiavelli's Prince, the “Arthashastra” written by Kautilya, prime minister of the founder of the Mauryan Empire, Chandragupta, whose grandson was Ashoka (see Kautilya, Machiavelli, Richelieu, Mazarin [to be published]).